Read more: NZ Parliament – Land Transport (Drug Driving) Amendment Bill | submissions on the bill

29 August 2024

Transport and Infrastructure Committee

Parliament Buildings

Wellington

Submission on the Land Transport (Drug Driving) Amendment Bill 2024

- This submission is from the National Organisation for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, New Zealand (Incorporated 1980). We would like to speak about this submission [done 2 Sept 2024 – watch video here].

- Our mission is to move public opinion sufficiently to legalise the responsible use of cannabis by adults, and to serve as an advocate for consumer safety. Our submission focusses on how this Bill and the drug driving testing regime relates to cannabis and the one-in-ten adults in New Zealand who are regular consumers, as well as the large majority of adults who have tried it on occasion; the vast majority of whom are responsible, otherwise law-abiding citizens who may be entrapped by poorly targeted roadside checkpoints intended to detect recent use rather than impairment.

- We have given submissions on previous drug driving amendments. NORML’s position remains –

- We support the intention to make driving safer and to remove impaired drivers from our roads and is supportive of impairment testing for drivers, with some caveats such as:

- That it is evidence based and an accurate predictor of impairment; and

- Not grounds for searches or spurious prosecutions for the use of drugs;

- We support treating cannabis consistently with alcohol and other prescription medications;

- We are opposed to per se approaches for cannabis, as they fail to recognise there is no correlation between levels of impairment and THC concentration in any bodily fluid;

- We are pleased that the medical defence (s64) remains for patients using medical cannabis under supervision of their prescriber, however we urge strengthening it so that proceedings are not brought to court;

- We urge strengthening s73A in the Act that a positive result cannot be used to initiate searches or bring proceedings for the use or consumption of drugs.

- We support the intention to make driving safer and to remove impaired drivers from our roads and is supportive of impairment testing for drivers, with some caveats such as:

4. The Bill under consideration –

- Allows the Minister of Police to approve inaccurate devices known to have false positives and false negatives; and

- Changes oral fluid tests from evidential to screening (and renames them accordingly).

5. A driver who fails two oral fluid screening devices is banned from driving for 12 hours and an evidential blood sample taken for lab analysis. 3ng/ml of THC is an infringement and 5ng/ml a criminal offence.

6. We are concerned that the proposed regime is a per se approach that will see unimpaired drivers fined or prosecuted while other impaired drivers fail to be detected.

7. NORML’s Principles of Responsible Cannabis Use includes No Driving While Impaired. However, per se traffic laws such as this make it a crime (or infringement) for a driver to operate a vehicle with trace levels of either THC or its metabolites in their blood or saliva, regardless of whether there exists any demonstrable evidence that the driver is under the influence.

8. We remain concerned about the reliability, intrusiveness, accuracy, and scope of using oral fluid devices; if these are to be authorised, we support only recording a “Fail” result upon two positive oral swabs, as this somewhat mitigates their inherent unreliability.

9. If blood tests are used for THC, cut off levels should be calibrated to reflect the same level of impairment as the alcohol BAC. We note research which suggests this should be in the range of 7-10ng/ml THC.

10. We strongly urge testing only for active ingredients like THC, not inactive metabolites such as THC-COOH which may linger for days or weeks after cessation of use.

11. We are concerned proposals to include ‘families of substances’ in testing regimes could include non-psychoactive cannabinoids (such as CBD) and/or non-psychoactive metabolites (such as THC-COOH), which would then capture an even greater number of unimpaired drivers.

12. The Attorney-General’s Section 7 report[1] noted that the Bill appears to be inconsistent with s 21 (right to be secure against unreasonable search and seizure) and s 22 (right not to be arbitrarily detained) and cannot be justified under s 5 of the Bill of Rights Act. We also believe these breaches cannot be justified because the proposed regime is not evidence based and is not an accurate predictor of impairment.

13. We advocate instead for technology-based approaches to mobile testing such as DRUID[2], enhanced use of the Compulsory Impairment Test, and better community education including a simple time-based awareness campaign: don’t drive for 4 hours after use.

Commentary

Objectives and consistency with drink-driving

14. The Land Transport (Drug Driving) Amendment Act 2022 established a random fluid testing regime for drivers, sitting alongside the Compulsory Impairment Test (CIT) approach to drug driving. A police officer can randomly stop anyone driving and administer an oral fluid (saliva) test. Cut-off thresholds would be set for the detection of drugs, and these would be aligned to the drink driving infringement penalty.

15. We called that first version of the testing regime “pretty good”[3]. We support regulating cannabis consistently with alcohol and prescription medications. We support the intention to make driving safer and to remove impaired drivers from our roads.[4]

16. The challenge is to accurately deter and detect impaired drivers, while not erroneously capturing non-impaired drivers. Many New Zealanders use cannabis regularly or on occasion. Some have legal access to medicinal cannabis products. Cannabis metabolites can linger in the body for weeks after consumption, but any impairment lasts just a few hours.

17. Experts appointed to set the cut off levels for impairment failed to do so; instead, the Act was amended so the devices could show ‘recent use’. Police still could not find devices that accurately show recent use. This amendment will allow the Minister of Police to approve devices that are not accurate; devices known to show false positives of innocent people and fail to identify significant numbers of impaired drivers.

18. ESR data provided to the Ministry of Transport and often cited by the Minister of Transport[5] counts drivers with any detectable presence of illicit drugs but includes alcohol only if over the legal limit. Indeed, the opening paragraph of this Bill says, “Over 2019–2022, an average of 105 people were killed each year in crashes after drivers had consumed impairing drugs, representing around 30% of all road deaths.” However, those are drivers showing any trace or residual amount – most would not be impaired. A more accurate figure would be counting only drug-positive drivers over a level comparable with New Zealand’s BAC.

19. We strongly support that the oral fluid screening devices and evidential blood test are all calibrated to an equivalent level of impairment as the current legal alcohol limit for driving – not simply ‘recent use’ or an arbitrary number that a device manufacturer happens to offer.

Evidence-based road policing? Numerous studies report that the detection of THC in blood or saliva is a poor predictor of impaired driving performance.

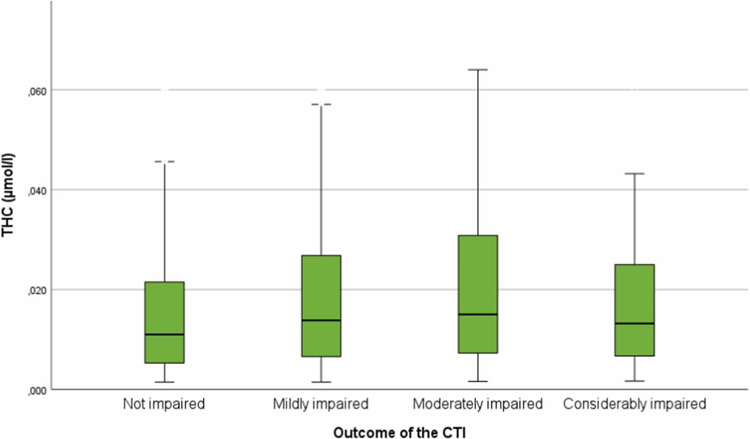

20. The Government claims this is evidence-based road policing. However, the weight of scientific evidence shows THC blood and saliva concentrations are not correlated with behavioural impairment.The latest such study was published August 2024 in Forensic Science International[6].

- Since 2022 all drivers in Norway suspected of being impaired by drugs including alcohol undergo a blood test and Clinical Test of Impairment performed by a physician. Their law specifies that THC in the blood at 3ng/ml is equivalent to a BAC of 0.05.

- Researchers assessed the relationship between drug concentrations and impaired psychomotor performance in more than 15,000 individuals found to have drugs in their blood and 3,684 drug-free controls.

- Consistent with prior literature, they found “the correlation between drug concentration was high for ethanol [and benzodiazepines], … but low for THC [and amphetamines].”

- Specifically, authors determined, “For THC, the median drug concentrations changed little between drivers assessed as not impaired and impaired.” The median THC of drivers assessed as being ‘considerably impaired’ was lower than the ‘moderately impaired’ drivers.

This is shown in Figure 3 of the study’s published report, below:

Hjelmeland et al, Caption: “Fig. 3. Boxplot of concentrations of … THC (green) at different levels of clinical impairment. The boxes represent the interquartile range (lower limit – 25th percentile; upper limit – 75th percentile), with the middle (black horizontal) line of the box representing the median concentration for each level of clinical impairment. The whiskers represent the range of the concentrations, not including outliers greater than 1.5 x the interquartile range.”

- The correlation was so poor, drivers who tested between 0.01 μmol/l (3ng/ml, the same as New Zealand) or 0.02 μmol/l (6ng/ml, ‘high risk’ and criminal enforcement in New Zealand) were then assessed by a doctor as either Not impaired, Mildly impaired, Moderately impaired or Considerably impaired. The drivers with the highest test results were assessed as Moderately impaired. Many of the Not impaired drivers would have failed the oral fluid and blood tests to be performed here.

- Only 49% of the drivers who failed THC blood tests were assessed as being impaired; only 10% were “obviously” impaired to the examining doctor. Alcohol, on the other hand, was strongly correlated between levels of ethanol in the blood and degree of impairment assessed by the physician.

- The study authors noted “The lack of a close relationship between drug concentration of THC and degree of impairment at the individual level is in accordance with several observations from experimental studies [where participants engaged in the] controlled intake of cannabis.”

- The results of a 2023 state-funded study[7] conducted by researchers affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, found neither the detection of THC nor its metabolites in subjects’ blood, breath, or oral fluid is correlated with psychomotor performance. Investigators assessed participants’ driving simulator performance at multiple points in time following their inhalation of cigarettes containing either moderate levels of THC (six percent), high levels of THC (13 percent), or no THC.

- Blood, oral fluid, and breath samples were collected from study subjects. Trained law enforcement officers also assessed subjects’ performance on Standard Field Sobriety Tests at various times following participants use of either cannabis or placebo.

- Authors concluded: “In the largest trial to date involving experienced users smoking cannabis, there was no correlation between THC (and related metabolites/cannabinoids) in blood, OF [oral fluid], or breath and driving performance. … The complete lack of a relationship between the concentration of the centrally active component of cannabis in blood, OF, and breath is strong evidence against the use of per se laws for cannabis.”

- A 2022 study[8] published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry also showed the detection of THC in blood is not correlated with changes in simulated driving performance. Investigators affiliated with the University of California, San Diego assessed subjects’ simulated driving performance after inhaling either low-potency (six percent), moderate-potency (13 percent), or placebo cannabis.

- Cannabis inhalation was not associated with any uptick in crash risk. Researchers identified no correlation between subjects’ blood/THC levels and driving performance at any point during the study. Consistent with prior studies, authors reported, “The current results reinforce that per se laws based on blood THC concentrations are not supported [by evidence].”

- Closer to home, in 2021 researchers at the University of Sydney published results[9] of a simulated driving study titled “The failings of per se limits to detect cannabis-induced driving impairment”. The clinical trial tested the validity of a range of blood and oral fluid THC per se limits in predicting driving impairment during a simulated driving task.

- A group of infrequent cannabis users were assessed at two timepoints (30 min and 3.5 h) under three different conditions: controlled vaporisation of 125 mg (i) THC-dominant cannabis (11% THC; <1% CBD), (ii) THC/CBD cannabis (11% THC; 11% CBD), and (iii) placebo cannabis (<1% THC & CBD).

- Plasma and oral fluid samples were collected before each driving assessment. Impairment was defined as an increase in standard deviation of lateral position (SDLP) of >2 cm.

- The researchers assessed whether per se limits of 1.4 and 7 ng/mL THC in plasma (meant to approximate 1 and 5 ng/mL whole blood) and 2 and 5 ng/mL THC in oral fluid reliably predicted impairment relative to placebo. These levels are close to, or the same as, those specified here.

- The results showed how “(i) impairment can be minimal in the presence of a positive THC result, and (ii) impairment can be profound in the presence of a negative THC result.”

- Study authors concluded “There appears to be a poor and inconsistent relationship between magnitude of impairment and THC concentrations in biological samples, meaning that per se limits cannot reliably discriminate between impaired from unimpaired drivers. There is a pressing need to develop improved methods of detecting cannabis intoxication and impairment.”

- An Australian meta-analysis published in 2021 in the journal Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews[10] reported that no consistent relationship exists between THC or THC-metabolite concentrations and impaired performance, and that such relationships are nearly impossible to infer in more habitual cannabis consumers. Further, they identified blood THC concentrations as “the poorest correlates of impairment, demonstrating a ‘very weak’ relationship after both ingestion and inhalation of THC.”.

- Authors cautioned that the imposition of so-called per se limits for the presence of THC in blood is ill advised because the laws are “unlikely to be effective in distinguishing between impaired and unimpaired (or not meaningfully-impaired) regular cannabis users” who may have residual levels of THC or its related metabolites for extended periods of time absent any actual impairment.

- Another 2021 literature review[11] published in the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry found the presence of THC concentrations in blood or saliva is an unreliable predictor of impaired driving performance. Researchers at Yale University assessed papers specific to the issue of cannabis and driving performance. As with prior reviews, they reported that the presence of THC in bodily fluids is not a consistent predictor of impairment and that statutory per se limits for THC are not evidence-based.

- Authors noted, “While legislators may wish for data showing straightforward relationships between blood THC levels and driving impairment that parallel those of alcohol, the widely different pharmacokinetic properties of the two substances … make this goal unrealistic.”

- They added: “[S]tudies suggest that efforts to establish per se limits for cannabis-impaired drivers based on blood THC values are still premature at this time. Considerably more evidence is needed before we can have an equivalent ‘BAC for THC.’ The particular pharmacokinetics of cannabis and its variable impairing effects on driving ability currently seem to argue that defining a standardized per se limit for THC will be a very difficult goal to achieve.”

- Another literature review in 2021[12], also published in the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry, found the presence of THC concentrations in blood is an unreliable predictor of impaired driving performance. After reviewing multiple scientific papers published over the last decade, researchers concluded, “[T]here is no clear overall relationship with THC blood or serum levels and driving skills or crash risk. … Not surprisingly, there is no unanimous agreement on potential THC legal cut-off levels. … Therefore, the various THC concentrations used to define a cannabis-related driving offense in EU [European Union] countries and some US-states varying between 1 and up to 7 ng/ml alone may not be appropriate to evaluate driving skill impairment comprehensively.”

- A 2019 report issued by the US Congressional Research Service[13] similarly determined: “Research studies have been unable to consistently correlate levels of marijuana consumption, or THC in a person’s body, and levels of impairment. Thus, some researchers, and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, have observed that using a measure of THC as evidence of a driver’s impairment is not supported by scientific evidence to date.”

- Another 2019 study published in the International Journal of Legal Medicine[14] found the presence of low levels of THC in blood is poorly correlated with driving performance. Researchers failed to identify any “reliable correlations” in the total quantity of cannabis consumed by participants and their THC blood concentrations immediately afterward, indicating “a considerable variation” in THC’s bioavailability. Authors also couldn’t find any reliable relationship between drivers’ THC levels and performance. They concluded: “Consistent with previous studies, a direct correlation between the individual fitness to drive and the THC concentrations … was not found. Therefore, determining a threshold limit for legal purposes based on these values alone seems to be arbitrary.”

- In Australian a 2004 multi-centre case-control study[15] was conducted on 3398 fatally-injured drivers to assess the effect of alcohol and drug use on the likelihood of them being culpable. Blood serum THC concentrations of up to 5ng were associated with an odds ratio of 0.7 compared to no-drugs. That is, drivers with up to 5ng THC were safer with less risk of crashing.

- NORML acknowledges some studies have shown that THC inhalation is associated with changes in driving behaviour, such as an increased likelihood of weaving[16] and a decrease a drivers’ average speed[17]. These and other changes are typically less pronounced in subjects who are more habitual cannabis consumers[18], but they may be exacerbated when alcohol and marijuana are ingested in combination with one another[19].

- It is worth noting that the ingestion of CBD-dominant cannabis strains has not been associated with any changes in driving performance. According to data[20] published in 2021 the journal Forensic Sciences Research, the inhalation of CBD-dominant cannabis flowers does not influence subjects’ reaction time, concentration, balance, time perception, or other skills associated with driving ability.

- A team of Swiss researchers assessed the influence of either CBD-dominant cannabis (16.6 percent CBD and 0.9 percent THC), or placebo, on a variety of neurocognitive and psychomotor skills. Researchers observed “no symptoms of impairment” and “no significant impact on driving ability” in study subjects who inhaled CBD-dominant cigarettes.

- Despite showing no impairment of performance, several subjects did nonetheless test positive for trace levels of THC in their blood 45 minutes after smoking. Authors cautioned that subjects’ elevated THC levels would place them in violation of certain traffic safety per se laws that criminalize the operation of a motor vehicle with detectable quantities of THC or THC metabolites in the driver’s bloodstream.

Additional issues with oral fluid testing devices

- In addition to being a very poor predictor of impaired driving performance, we have previously expressed other concerns[21] about oral fluid testing or screening devices:

- Current devices show a high number of false positives and false negatives. An Australian study[22] examined the reliability and accuracy of two commonly used devices, the Securetec DrugWipe® 5 s (DW5s) and Dräger DrugTest® 5000 (DT5000). It found:

“5% of DW5s test results were false positives and 16% false negatives. For the DT5000, 10% of test results were false positives and 9% false negatives. Neither the DW5s nor the DT5000 demonstrated the recommended >80% sensitivity, specificity and accuracy”;

- Each oral swab will cost several times what it costs to perform an alcohol breath test. Transport Minister Simeon Brown recently announced[23] $20 million in funding over 3 years to perform 50,000 roadside oral tests annual, implying it will cost $133 per test;

- It is a significant inconvenience to drivers – and impractical for law enforcement – if roadside tests take longer than a moment to complete;

- Detection may be avoided or manipulated, as drug residues in saliva can be washed out to varying degrees by drinking or eating food, chewing gum, masking with low alcohol or mouthwash, taking drugs in ways that avoid leaving residues in the mouth (eg swallowing capsules or using topicals), or encouraging the use of more risky but non-tested drugs such as Novel Psychoactive Substances;

- Expecting police officers to handle bodily fluids is very invasive with risk of spreading bacteria or viruses (including COVID-19) if the hygiene controls are not ‘up to scratch’;

- Since testing is at the parts-per-billion level, there is significant risk of cross-contamination from handling samples of other drivers or touching contaminated work surfaces;

- Many people may feel uncomfortable having non-medical personnel forcing bodily fluids from them on the roadside;

- Currently available oral swabs do not detect drugs highly indicated in impairment such as synthetic cannabinoids. They may therefore encourage the use in synthetics or other drugs that cannot be detected or are flushed more quickly – yet may be riskier;

- In the absence of reliable accurate devices, we cautiously support only recording a “Fail” result upon two positive oral swabs, as this mitigates to some degree their inherent unreliability.

The Bill of Rights Act

- This Bill codifies a process where any driver going about their business may be stopped, without reason, and subjected to a search of their oral fluids, and/or made to perform various physical activities, and/or compelled to give a sample of their blood for evidential purposes. These breach the principles of natural justice and s21, s22 and s25(c) of the Bill of Rights Act 1990, which affirms the right to be free from arbitrary detention, unreasonable search and seizure, and to be presumed innocent until proven guilty.

- Any such breaches of the fundamental rights of citizens must be justified, and while this has arguably been demonstrated in the case of alcohol checkpoints, the evidence is far less clear for cannabis.

- We recognise the Bill attempts several balancing acts and places some important limits on what the police can do. However, any personal or institutional biases are more likely to impact Māori and young males.

- We support the provision that makes clear a positive result cannot be used evidentially for an additional charge of possession or use (s73A). However, we remain concerned a positive result (of any test) could be used by officers to conduct searches of persons or vehicles. Such a search would be a “fishing trip” as confirmation of impairment is not evidence of possession at the time.

- We recommend strengthening s73A by adding a provision to ensure any positive results cannot be used to initiate searches (noting, this would not bar any other grounds for searches).

Alternatives to bodily fluid testing

- As a result of these concerns and the weight of scientific evidence, NORML has long opposed[24] the imposition of per se THC limits for motorists and has alternatively called for the expanded use of mobile performance technology like DRUID[25] and Alertmeter[26].

- We also support enhanced use of the current Compulsory Impairment Test (CIT). This includes an eye assessment, a walk and turn, and a one leg stand assessment. When properly administered it can be a more accurate predictor of impairment from any cause (drugs, alcohol, fatigue, medicines etc).

- However, we remain concerned at the potential for biased enforcement and agree CITs must not be used evidentially. Due to the subjective nature of the test, an officer could fail people they do not like. The impact of inherent bias on an observational test must be considered – for example, it is likely there will be an overall negative bias towards Māori and young males.

- Therefore, we recommend more training and oversight for officers, and that body or dash cams be made mandatory during testing so that any test is recorded and can be made available for any court proceedings. An impartial visual recording of any impairment would help alleviate concerns around biased enforcement.

- We encourage considering new non-invasive technology-based solutions to better measure impairment, such as with a handheld device fitted with sensors and connectivity or an app that can be used on any smart phone – by law enforcement or by drivers to self-test before they drive. For examples see the DRUID or Alertmeter apps developed to assess a user’s level of impairment due to any cause.

- Recent news reports stated NZ Transport Agency Waka Kotahi, with support of the Police and Worksafe, has approved the use of the Alertmeter app for livestock truckers[27]. The one-minute test, developed by PredictiveSafety in the United States, resembles a video game and tests alertness and reaction time regardless of the cause – including fatigue. This and/or DRUID should be encouraged for more road users.

- We lament additional funding for training, dash cams and developing new technology could have come from levies on the sale of legal cannabis products for adult use. We recommend funding should be made available to support the development or adoption of dash cams and new technology such as DRUID.

- We recommend consideration of a 2007 international working group of experts on issues related to drug use and traffic safety, who evaluated evidence from experimental and epidemiological research and discussed potential approaches to developing per se limits for cannabis. They noted:

“A comparison of meta-analyses of experimental studies on the impairment of driving-relevant skills by alcohol or cannabis suggests that a THC concentration in the serum of 7-10 ng/ml is correlated with an impairment comparable to that caused by a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.05%. Thus, a suitable numerical limit for THC in serum may fall in that range.”[28]

- We note German researchers[29] found “no correlation” between THC levels in blood and psychomotor impairment, and instead found the point in time after cannabis consumption to be a much stronger predictor of impairment. In contrast, researchers from the University of British Columbia[30] found the detection of THC in blood at levels greater than 2ng/ml may persist for extended periods of time, and therefore it is not necessarily indicative of recent cannabis exposure.

- Recent research from the Lambert Initiative[31] in Australia suggests the actual impact on driving ability varies considerably between individuals and may relate not only to dosage and time interval, but also their experience both with cannabis and with driving. Novices in either tend to fare worse, but for most people impairment typically lasts from 2 to 4 hours. They note a simple education message to get across to drivers: don’t drive for 4 hours after use. We would welcome an education campaign that included such messages.

Thank you for considering this submission and giving us the opportunity to present our views.

Yours faithfully,

Chris Fowlie

President,

NORML New Zealand Inc

[1] Report of the Attorney-General under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 on the Land Transport (Drug Driving)

Amendment Bill Presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to Section 7 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 and Standing Order 269 of the Standing Orders of the House of Representatives. Available at https://bills.parliament.nz/v/4/4a1add47-2008-4fa0-75b4-08dcaf6f1ee5

[2] More information about DRUID is available at https://www.impairmentscience.com/

[3] https://norml.org.nz/govt-roadside-drug-testing-shock-the-proposed-rules-are-actually-pretty-good%ef%bb%bf/

[4] https://norml.org.nz/about/responsible-use/ “The responsible cannabis consumer does not operate a motor vehicle or other dangerous machinery impaired by cannabis, nor (like other responsible citizens) impaired by any other substance or condition, including some medicines and fatigue. Although cannabis is said by most experts to be safer than alcohol and many prescription drugs with motorists, responsible cannabis consumers never operate motor vehicles in an impaired condition. Public safety demands not only that impaired drivers be taken off the road, but that objective measures of impairment be developed and used, rather than chemical testing.”

[5] https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/drunk-and-drugged-drivers-targeted-new-road-policing-programme

[6] Knut Hjelmeland, Gerrit Middelkoop, Jørg Mørland, Gudrun Høiseth, The relationship between clinical impairment and blood drug concentration: Comparison between the most prevalent traffic relevant drug groups, Forensic Science International, Volume 363, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2024.112180.

[7] Fitzgerald RL, Umlauf A, Hubbard JA, Hoffman MA, Sobolesky PM, Ellis SE, Grelotti DJ, Suhandynata RT, Huestis MA, Grant I, Marcotte TD. Driving Under the Influence of Cannabis: Impact of Combining Toxicology Testing with Field Sobriety Tests. Clin Chem. 2023 Jul 5;69(7):724-733. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvad054. Erratum in: Clin Chem. 2024 Mar 2;70(3):569. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvad218. PMID: 37228223; PMCID: PMC10320013.

[8] Marcotte TD, Umlauf A, Grelotti DJ, et al. Driving Performance and Cannabis Users’ Perception of Safety: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(3):201–209. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4037

[9] Arkell TR, Spindle TR, Kevin RC, Vandrey R, McGregor IS. The failings of per se limits to detect cannabis-induced driving impairment: Results from a simulated driving study. Traffic Inj Prev. 2021;22(2):102-107. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2020.1851685. Epub 2021 Feb 5. PMID: 33544004

[10] McCartney D, Arkell TR, Irwin C, Kevin RC, McGregor IS. Are blood and oral fluid Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and metabolite concentrations related to impairment? A meta-regression analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022 Mar;134:104433. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.004. Epub 2021 Nov 9. PMID: 34767878.

[11] Pearlson Godfrey D, Stevens Michael C, D’Souza Deepak Cyril. Cannabis and Driving. Frontiers in Psychiatry, Vol 12, 2021. DOI=10.3389/fpsyt.2021.689444 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.689444

[12] Preuss Ulrich W., Huestis Marilyn A., Schneider Miriam, Hermann Derik, Lutz Beat, Hasan Alkomiet, Kambeitz Joseph, Wong Jessica W. M., Hoch Eva. Cannabis Use and Car Crashes: A Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, Vol 12, 2021. DOI=10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643315 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643315

[13] Congressional Research Service, Marijuana Use and Highway Safety, May 14, 2019. R45719. Available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45719

[14] Tank A, Tietz T, Daldrup T, Schwender H, Hellen F, Ritz-Timme S, Hartung B. On the impact of cannabis consumption on traffic safety: a driving simulator study with habitual cannabis consumers. Int J Legal Med. 2019 Sep;133(5):1411-1420. doi: 10.1007/s00414-019-02006-3. Epub 2019 Jan 30. PMID: 30701315.

[15] Drummer OH, Gerostamoulos J, Batziris H, Chu M, Caplehorn J, Robertson MD, Swann P. The involvement of drugs in drivers of motor vehicles killed in Australian road traffic crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2004 Mar;36(2):239-48. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00153-7. PMID: 14642878. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14642878/

[16] https://norml.org/marijuana/library/cannabis-and-driving-a-scientific-and-rational-review/

[17] Simmons SM, Caird JK, Sterzer F, Asbridge M. The effects of cannabis and alcohol on driving performance and driver behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2022 Jul;117(7):1843-1856. doi: 10.1111/add.15770. Epub 2022 Jan 26. PMID: 35083810. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35083810/

[18] Brooks-Russell A, Brown T, Friedman K, Wrobel J, Schwarz J, Dooley G, Ryall KA, Steinhart B, Amioka E, Milavetz G, Sam Wang G, Kosnett MJ. Simulated driving performance among daily and occasional cannabis users. Accid Anal Prev. 2021 Sep;160:106326. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2021.106326. Epub 2021 Aug 14. PMID: 34403895; PMCID: PMC8409327. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34403895/

[19] Fares A, Wright M, Matheson J, Mann RE, Stoduto G, Le Foll B, Wickens CM, Brands B, Di Ciano P. Effects of combining alcohol and cannabis on driving, breath alcohol level, blood THC, cognition, and subjective effects: A narrative review. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022 Dec;30(6):1036-1049. doi: 10.1037/pha0000533. Epub 2022 Jan 20. PMID: 35049320. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35049320/

[20] Gelmi TJ, Weinmann W, Pfäffli M. Impact of smoking cannabidiol (CBD)-rich marijuana on driving ability. Forensic Sci Res. 2021 Sep 28;6(3):195-207. doi: 10.1080/20961790.2021.1946924. PMID: 34868711; PMCID: PMC8635612.

[21] https://norml.org.nz/normls-submission-to-nzta-on-drug-impaired-driver-testing/

[22] Arkell et al, Detection of Δ9 THC in oral fluid following vaporized cannabis with varied cannabidiol (CBD) content: An evaluation of two point‐of‐collection testing devices. Drug Testing and Analysis, 11.10 October 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2687 See also https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2019/09/12/study-casts-doubt-on-accuracy-of-mobile-drug-testing-devices-.html

[23] https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/drunk-and-drugged-drivers-targeted-new-road-policing-programme

[24] Armentano, Paul: Cannabis and Driving: A Scientific and Rational Review. https://norml.org/marijuana/library/cannabis-and-driving-a-scientific-and-rational-review/. Additional information is available from the Fact Sheet, ‘Marijuana and Psychomotor Performance’ available at https://norml.org/marijuana/fact-sheets/marijuana-and-psychomotor-performance/

[25] DRUID app https://impairmentscience.com/

[26] Alertmeter app https://predictivesafety.com/alertmeter/

[27] Radio New Zealand, Trial on changing truck driver requirements could go nationwide, 7 May 2024. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/country/516161/trial-on-changing-truck-driver-requirements-could-go-nationwide and Farmer’s Weekly, ‘Video game’ app tests driver fatigue, 2 November 2023. https://www.farmersweekly.co.nz/technology/video-game-app-tests-driver-fatigue/

[28] Grotenhermen, F. et al. Developing limits for driving under cannabis. Addiction. 2007 Dec;102(12):1910-7. Epub 2007 Oct 4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17916224

[29] Tank A et al. On the impact of cannabis consumption on traffic safety: a driving simulator study with habitual cannabis consumers. Int J Legal Med. 2019 Sep;133(5):1411-1420. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30701315/;

[30] Peng YW, et al. Residual blood THC levels in frequent cannabis users after over four hours of abstinence: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020 Nov 1;216:108177. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32841811/;

[31] McCartney et al, Determining the magnitude and duration of acute Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC)-induced driving and cognitive impairment: A systematic and meta-analytic review, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Volume 126, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.003