OPINION By Chris Fowlie. First published on The Daily Blog, November 7, 2021.

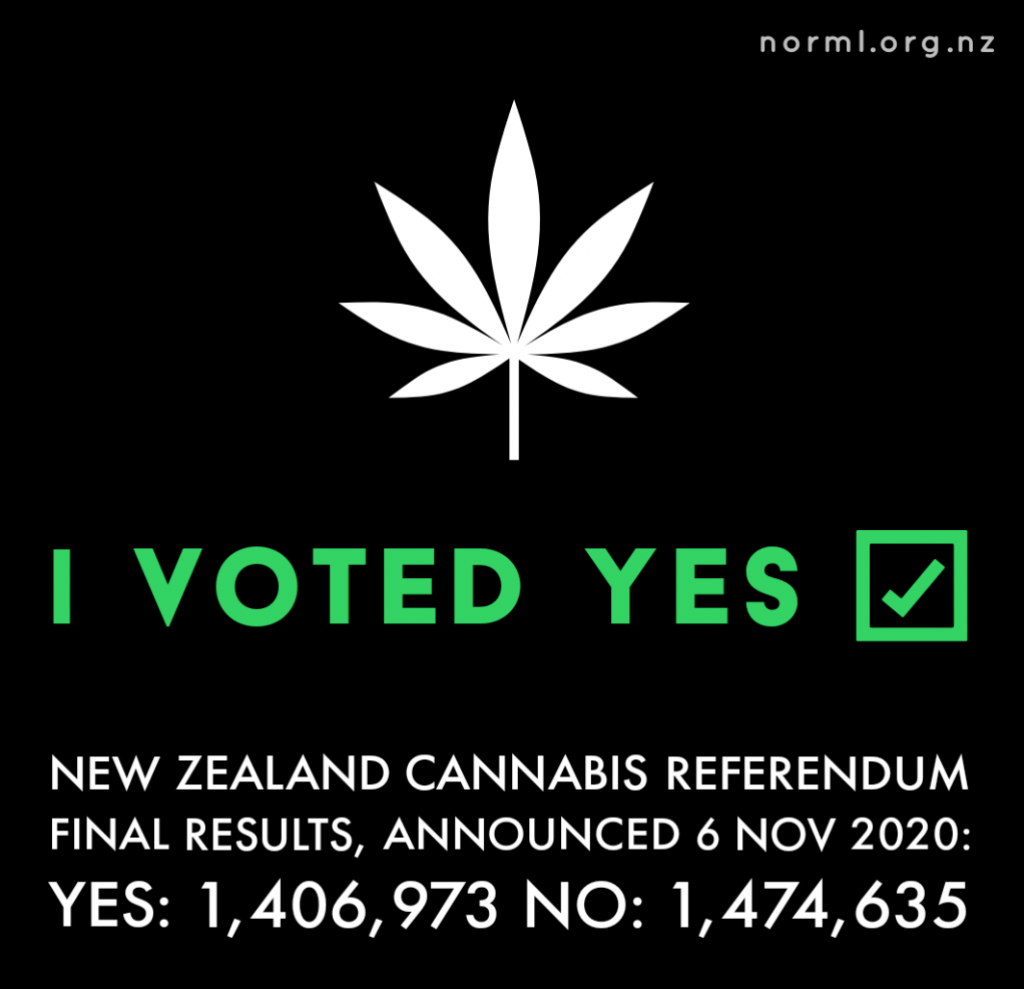

This weekend the Labour Party held their annual conference. It’s also one year since the announcement of the results of their cannabis referendum, in which a forgotten 48 per cent of voters supported full commercial legalisation.

A lot has happened since then – mostly related to Covid – but there has been almost no progress on cannabis law reform. In many respects it has gone backwards. What happened to the needs and wishes of the 1,406,973 Kiwis who voted Yes – have they really been entirely forgotten?

It seems Andrew Little, who ran the referendum and now runs the Ministry of Health – has been true to his word. He had pledged cannabis reform would be off the agenda if No won.

But as I’ve previously written here, there are many things the government could do to soften the current approach and recognise the widespread consensus for treating cannabis use as a health issue, not a crime. So, what has happened since last year’s vote?

Cannabis arrests have declined – but inequities remain.

While the law didn’t change, police heeded the message anyway. Most politicians don’t want to do anything about it, but Maori remain more likely to be arrested and prosecuted for the same thing. There are also widespread regional differences, with Aucklanders up to ten times more likely to be arrested than Southlanders. Police discretion can be a wonderful thing, but it has clearly failed here. Police need clear guidance and policy statements of what is expected – like the tolerance for going a few k’s over the speed limit – rather than leaving it to the judgement of individual officers.

The Law Commission called for mandatory warnings, not police discretion. If history has taught us anything, it is that law enforcement needs clear bounds and if there is a policy vacuum, they will fill it with arrests. Rather than abdicating responsibility and leaving it to individual officers to decide, Health Minister Andrew Williams and Police Minister Poto Williams should declare what they expect of police and the public, in very specific terms. For example, the presumptions of supply for cannabis in the existing law are possession of up to 28 grams and growing up to 10 plants – so tell police to give warnings for amounts below that.

Tax revenue foregone, and public health risks.

The US state of Illinois, which legalised cannabis last year along similar lines as NZ’s referendum, just raked up US$1 billion in sales so far in 2021. Cannabis brings in more tax revenue than alcohol. They are using it for social equity provisions, helping those most impacted by previous policies, funding street violence prevention programs, and wiping historic cannabis convictions.

Meanwhile the illicit market in Aotearoa has continued unabated despite the No vote and seems to not have been impacted by Covid lockdowns. Keeping cannabis illicit may even have contributed to some Covid spread, as many transactions still happen face to face, and providers who don’t follow rules are to be expected in illicit markets. From a public health perspective, decriminalisation of drugs should be considered as part of the response to Covid. At the very least, a public statement that Police would not pursue delivery services or providers operating online would be helpful here.

Medicinal cannabis remains expensive and out of reach.

The strict pharmaceutical approach of our medicinal scheme was based on a presumption of the referendum passing. As it was being developed everyone thought Yes would pass, including officials that I met. Patients would be able to buy herbal flowers from cannabis stores, they said, so there would be no need to have a herbal pathway for doctors to prescribe. Patients would also be able to grow their own, like anyone else aged over 18, and Green Fairies could share their wares like anyone else, so they didn’t need protection. But of course, none of that happened. Instead, we are left with a Big Pharma-loving scheme that has no place for herbalists, caregivers, Green Fairies, old school growers, hemp farmers, or anyone who doesn’t have a share market listing or the backing of a billionaire.

Recent weeks have seen the removal of most CBD products from the NZ market, the refusal of Andrew Little to extend the transition arrangementsthat allowed continued patient access, the rejection of an amnesty by Mr Little, Medsafe threatening doctors who import medicinal cannabis products for their patients, a third NZX listing of a cannabis company (this time Green Fern Industries), the approval of NZ’s first “local” medicinal cannabis products (imported CBD oil re-bottled by Helius with the $48 million bankrolled by their US-Kiwi billionaire investor, Guy Haddleton, to compete with the imported CBD made by Tilray, owned by the Canadian-Kiwi billionaire Peter Theil), and the announcement by Agriculture Minister Damien O’Connor of a $760,000 grant to foreign-owned Greenlab, which operates from a Lincoln University lab, to study NZ cannabis genetics and work out how to grow them best (GreenLab have promised to share the results of this taxpayer-funded study, but it is unclear if this is a requirement of the taxpayer funding).

There is very little happening here that directly benefits patients. It pains me to talk with colleagues in Australia and Columbia, as I did this week, and discover that Australian patients have access to hundreds of products including dozens of strains of flowers. We don’t. Australian suppliers can import crude extracts from Columbia then refine them in Australia, making products cheaper than would otherwise be the case. We can’t do that here. Australian pharmacies can do compounding, which may involve taking bulk sacks of flower, or drums of oil and selling by the gram to patients – cutting out middlemen and providing what patients what. New Zealand pharmacies can’t do that.

The Government should apply the Commerce Commission’s thinking around supermarkets to the medicinal cannabis industry. Current rules are favouring Big Pharma operations and causing similar problems as the supermarket duopoly: higher prices, reduced choice, our best produce going offshore, massive barriers to entry, using market dominance to stifle competition. I’ve written in more detail about that here with five changes in this area that could make a huge difference: let patients and caregivers import prescriptions that cannot be filled here, or let them grow by extending the palliative care defence to cultivation; revise the ludicrous product quality standards that are the toughest in the world (preventing access and raising prices); break up the large verticals by stopping them from both growing and manufacturing; allow pharmacies to compound bulk supplies like they can in Australia, the UK and Germany; and bring back the herbal pathway that was originally proposed for making and prescribing herbal cannabis products.

Access to medicinal cannabis remains an equity issue – it is limited to those who can afford it. Access to participating in the industry and enjoying any economic benefits is also an equity issue – it is limited to those with a share market listing or billionaire in their pocket.

New Zealand voted No by the narrowest of margins. You can be sure that if the shoe was on the other foot – if Yes had squeaked in by a tiny sliver – then that Cannabis Legalisation and Control Bill would have been watered down to take account of such a narrow victory. Just such a lens should be applied to the continued prohibition of cannabis, the effects of which are not experienced evenly.

—

Chris Fowlie is the president of the National Organisation for the Reform of Marijuana Laws NZ Inc; developer of the CHOISE model for cannabis social equity; CEO of Zeacann Limited, a cannabis science company; co-founder of the New Zealand Medical Cannabis Council; co-founder of The Hempstore Aotearoa; resident expert for Marijuana Media on 95bFM; cannabis blogger for The Daily Blog, and court-recognised independent expert witness for cannabis. The opinions expressed here are his own.